At a tiny sushi counter in this boundless capital’s southwest suburbs, nine of us sat silent and alert waiting for Koji Kimura to finish readying his lunchtime service.

We whispered our drink orders to the restaurant’s lone server while listening to indistinct sounds of cooking — running water, the muffled thud of a cleaver — coming from the kitchen hidden behind a red curtain. A few minutes later, Kimura appeared wordlessly, bowed to us and doled out small cups of clam soup distilled into a cloudy liquor.

And we were off.

Out of thousands of sushi chefs in Japan’s capital, Kimura has distinguished himself for his extreme approach to aging fish. He dove into developing his techniques a few years after he opened on this quiet street in the Futako-Tamagawa neighborhood in 2005. He was attracting few customers; he hated throwing away pounds of fish he bought from Tsukiji Market at dawn.

This is your guide to what the best sushi city in America has to offer, from the ultimate California roll to spectacular omakase.

He began to experiment with how time, cold air and natural enzymatic processes could lead to intensified flavors and suppler textures in seafood, similar to dry-aging steaks. Curious chefs eventually heard about his unorthodoxy and showed up at the restaurant’s counter, then told others. Sushi Kimura burgeoned into a Michelin-starred phenomenon.

I had been wanting to try Kimura’s renegade artistry for years.

Since Japan reopened for tourism in October, droves of eager, Insta-ready travelers, including me, have been rushing to immerse themselves. Sushi Kimura’s excellence and individualism turned my thoughts back toward home, though. I saw reflections of similar ambitions in L.A.’s most energized sushi chefs. It’s a dance between honoring the cuisine’s origin, nudging Angelenos’ ever-evolving tastes forward and trusting in one’s self-expression.

A dozen small appetizers preceded the nigiri that afternoon. Among them: a wild, mulchy mound of seaweed, creamed with mascarpone and blue cheese, that short-circuited my preconceptions in the best ways; and a risotto of sorts with pureed shirako (cod milt) and a dusting of tingly sansho, creating the creamy-peppery effect of a madcap cacio e pepe. The first-act finale was watari kani (raw blue crab) salt-pickled, marinated in brandy sauce and served among its mustardy innards with lemony sansho leaves.

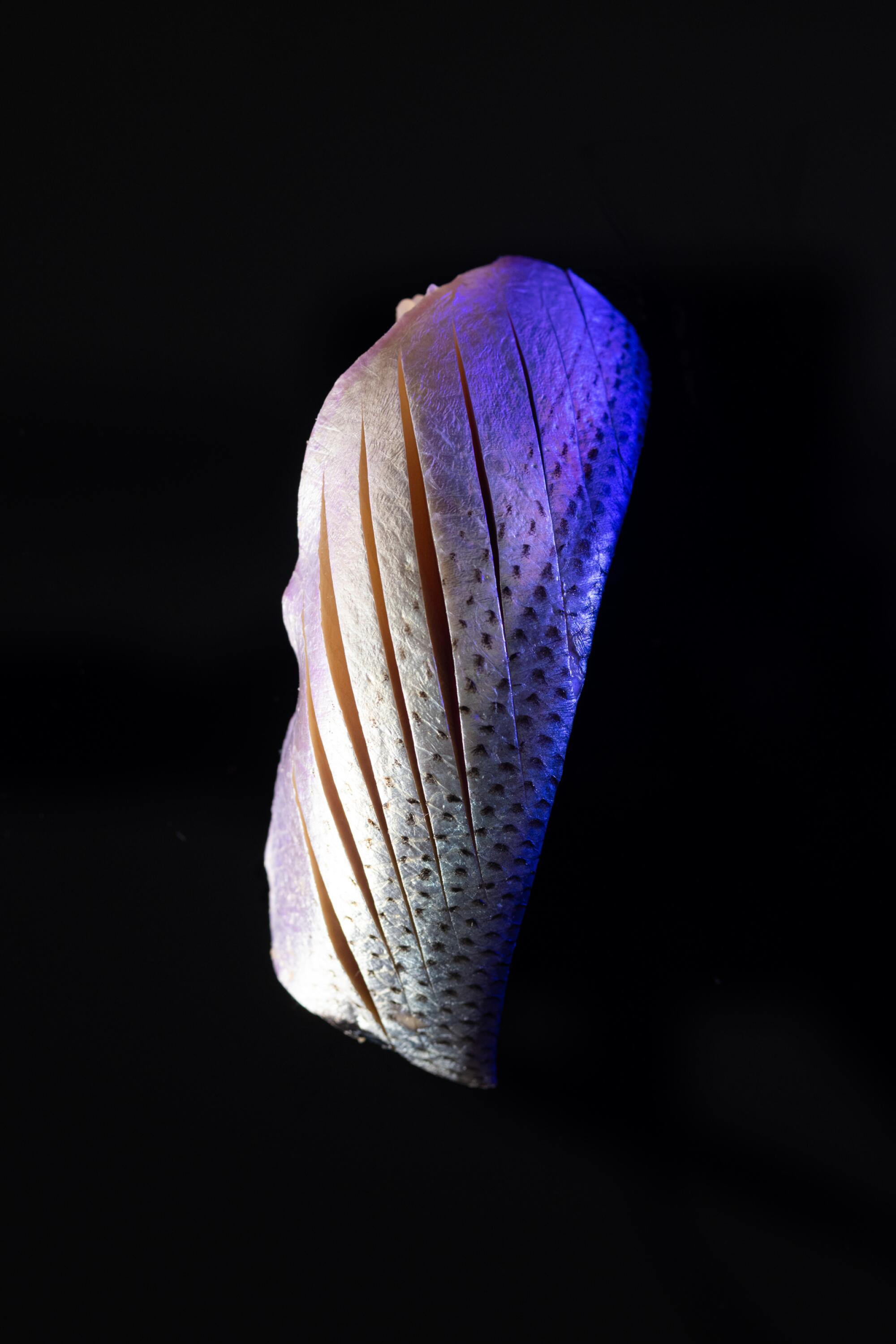

Kimura began making nigiri. He set down each piece and murmured the age of the fish in Japanese or English: “Sayori, needlefish, aged one week.” “Shima-aji, striped jack, aged one month.” “Aji, horse mackerel, aged three days.” “King salmon from Hokkaido, aged 14 days.”

He alternated between fresher and more matured examples to emphasize contrasts. The mackerel registered as crisp and sharp next to the month-old shima-aji, which had mellowed to the softness of a just-ripe banana, a substance my tongue could smash. He reached the showstopper: marlin, aged 49 days. It tasted like cultured butter transformed into marine life.

The fish was a revelation of delicious extremes. But there was also a midpoint during the lunch at Sushi Kimura that left just as profound an impact.

The owner of the Joint talks seafood, preservation and a sprawling new facility that will bring dry-aged fish to the masses.

After the crab and before the first round of nigiri, Kimura handed out a U-shaped sheet of nori filled only with shari, the seasoned sushi rice he would unite with fish. The grains were on the firm side, pleasantly so, and they buzzed with umami amplified from the sour and the sweet of two types of vinegar.

The intent behind this bite was unspoken but explicit: You’ve come for the aged fish. But sushi is a harmony. Notice the rice too, how it’s been calibrated especially for this seafood.

It wasn’t my first sushi meal at which a chef conveyed the equal importance of shari to neta (nigiri toppings), but it was the only time I’ve been fed rice as a preamble specifically to underscore its value.

In Tokyo, the sushi experiences are infinite. I disappeared into a dozen of them during an early-spring trip. In their sum, I grasped what has recently been driving excellence in L.A.’s own sushi ecosystem: an inspired return to the fundamentals.

Los Angeles will never be a land of absolutisms. For every chef taking the zaniest liberties, there will be another avowing the most exacting traditional practices. Among the city’s current generation of omakase chefs, though, I notice a new paradigm: More of them are returning the essence of the cuisine in their pursuit of greatness, and they have an engaged, ready audience.

L.A. sushi, in communion

Sushi is elemental to the story of Los Angeles. The California roll, the advent of supermarket sushi, the opening of the first local Japanese seafood distributor in 1963, the 1980s economic boom that flooded Los Angeles with Japanese capital, the Hollywood obsession with Matsuhisa in Beverly Hills, the now-ubiquity of sushi bars across the region: L.A.’s notions of nigiri and maki evolve in step with the city’s stacked identities. We have cultivated one of the world’s most fervent sushi cultures.

More than ever, that includes the headiest expressions. In a moment when ideas around “fine dining” — particularly in a Eurocentric, white tablecloth sense — are changing and dismantling globally, our omakase restaurants have never been more prominent, nor greater in number.

Omakase is an abbreviation of the Japanese phrase “omakase shimasu,” or “I’ll leave it up to you.” At an intimate counter, for a few hours, the customer yields decision-making. Rather than a grand whirl of servers, the staff numbers few. The hyperfocus underscores the quality of the ingredients and a skilled chef’s rigor. It’s a choreographed performance, and yet the exchange between shaping and eating nigiri also feels like a communion.

At a handful of L.A.’s standout sushi bars, an omakase reservation takes you straight to the nigiri. I’m thinking particularly of underrated Matsumoto, obscured in a Beverly Boulevard strip mall. You’re not even quite settled in front of Naruki Matsumoto when his hands go straight to work. He groups thumb-size pieces three to a plate, arranged in gradations of mild to stronger, or by fishes that he lightly torches, like nodoguro (blackthroat seaperch, a fat-rich favorite among chefs) and golden-eye snapper, or in a trio of lacy meat from Hokkaido hairy crab, flanked by two types of shrimp. It’s unusual for a chef of his caliber not to hand the customer nigiri portion by portion, but I always wind up appreciating his rhythm.

In the city’s tiniest temples of omakase — the ones with fewer than than a dozen seats, bookings fill within moments of their monthly release dates — the meals, like the one at Sushi Kimura, lean more to elaborate orchestrations.

Sakae Sushi has been making simple, homestyle sushi in Gardena since the 1960s. Every piece on the six-item menu is inexpensive and delicious.

At Sushi I-naba in Torrance, one of Yasuhiro Hirano’s marquee openers is nutty, daily-made soba swirled into a cool, mineral-sweet uni broth, a teaser for the generous globs of sea urchin arriving later in the meal. Yoshiyuki Inoue is poetic with chawanmushi; at Sushi Kaneyoshi in Little Tokyo, he might steam the custard with lacy meat from Hokkaido hairy crab, overlaid with a soft gelée that’s flecked with frilly seaweed. Across the street at Sushi Takeda, Hideyuki Takeda smokes meaty slices of katsuo (skipjack tuna) in hay and serves them under a glass dome filled with an extra hit of hickory smoke.

Variations on the appetizers-to-nigiri tasting menu have prevailed in Los Angeles for decades. In conversations with Brandon Hayato Go, who owns the seven-seat modern Japanese wonder Hayato and who began working at his father’s sushi bar in Seal Beach as a teenager, he refers to the progression as “sushi-kaiseki.” Go points to Masa Takayama and his menu at Ginza Sushi-Ko (the Beverly Hills predecessor, opened in 1987, to New York’s exorbitant Masa, which Takayama opened in 2004) as a major codifying force in Southern California omakase.

Takayama, in his L.A. prime, was a showman. He secured pristine seafood from Japan before today’s light-speed technology made such transactions far easier. More famously, he incorporated Western signifiers of luxury into his repertoire: tuna tartare heaped with Osetra caviar, foie gras bobbing in dashi, edible gold leaf draped over sliced beef, a climactic neta of seared wagyu.

Sushi’s norm-busting journey from culinary curiosity to mainstream L.A. offering was set in motion in the 1960s by two friends bound by a love for food.

A lot of glittery nigiri followed in his wake, and though Takayama wouldn’t have used it, a dab of truffle oil became a common gilding in sushi bars across town.

Sushi’s rich etymology

Over the last five years, as omakase-specific restaurants have inched regionally into the dozens, I’ve heard the word “Edomae” increasingly bandied around. It’s meant to evoke dedication to purity, but its context can be vague.

Edo, the name for Tokyo before 1868, means “mouth of the bay.” Mae translates as “in front of” or “before.” Beyond a literal connotation of “by the waterfront,” the term also generally denotes “in the style of Edo.” Historians often pinpoint the early 19th century as when nigirizushi emerged as a popular street food served from wooden stalls. Without refrigeration, fish was preserved by curing or pickling or boiling and served over salted, vinegared rice.

The food soon became synonymous with Tokyo. In “Oishii: The History of Sushi,” Eric C. Rath notes that after World War II, the Japanese government stepped in to formalize sushi training and apprenticeship. The advent of refrigeration gave Tokyo chefs flexibility and variety, and helped move sushi dining indoors.

“Edomae sushi” remained shorthand for an ideal. To its most stringent practitioners it meant using seafood caught only from Tokyo Bay, served in an environment, hearkening to its fast-service roots, where chatter was discouraged. Today its use more generally circles awareness of seasonality and an embrace of canonical techniques.

“Trying to define Edomae sushi is difficult, even for me,” writes Tokyo sushi master Kikuo Shimizu, in the English translation of his book “Edomae Sushi: Art, Tradition, Simplicity.” “After some 50 years as a chef, I’ve come to realize that a clear and simple textbook definition is practically impossible. In the broadest terms, however, I’d have to say: ‘Edomae sushi is what an expert sushi chef makes by hand out of Japanese ingredients.’”

At L.A.’s leading omakase restaurants — Kaneyoshi, I-naba, Shin Sushi in Encino and recently relocated Shunji in Santa Monica among them — the spirit of Edomae has meant sidestepping showy garnishes and doubling down on time-honored techniques. In sushi traditions, the neta has never been just about “raw fish.” It’s about what best frames the qualities of each variety: Marinate silvery kohada, grill or smoke ruby katsuo, boil prawns, preserve sea bream in seaweed, simmer eel, serve clams straight from their shells. A dot of freshly grated wasabi and a light brush of nikiri (soy sauce mixed with dashi, mirin and sake) finish nigiri the way a signature and varnish complete a painting.

All these elements — the specific consideration of each nigiri topping, a sense of playfulness in the dishes that kick off a meal — culminate at Morihiro Onodera’s sushi bar in Atwater Village. Onodera arrived in Los Angeles in 1985; among his peers, he is the working chef who lastingly continues to shape the notion of omakase as fine dining in the city.

His most enduring contribution may be his devotion to rice.

Onodera has been vocal about the significance of shari for decades. He likes to say that the rice is 60% of the flavor of sushi. The sentiment echoes the philosophy of Tokyo chef Jiro Ono, whose name remains synonymous as the benchmark of Edomae standards 11 years after the release of the documentary “Jiro Dreams of Sushi.”

Onodera opened Morihiro Sushi in 2020, his first restaurant after closing his West L.A. restaurant Mori Sushi, one of the city’s defining omakase restaurants, in 2011. He commissions his crop of rice from a farm in Japan’s Iwate prefecture, the region along the northeast coast of the country’s main island where he grew up. He polishes the unhulled grains daily using a milling machine.

I’m not aware of any other local sushi chef quite so dedicated. When he began making nigiri during my first meal at Morihiro, his shari stood out not only in taste but in tint. It glowed reddish-brown underneath pale flounder. Rather than the more common kome-zu, or rice vinegar, Onodera uses akazu, a red vinegar made from sake lees that traces back to Edomae traditions. Akazu has grown rarer due to its long fermentation period, at least three to four years, which makes it more expensive to produce — and also, in recent years, more desired by sushi chefs in North America.

The akazu that Onodera sprinkles over just-cooked rice ages for 10 years. It imparts a plummy mix of sour, sweet and salty. The taste hits the brain for a nanosecond, at the same time the palate registers the dancing texture of the distinct grains. The effect merges with the neta as both seasoning and counterpoint. It’s subtle, and in the minimalist perfection of nigiri, practical.

L.A. will always have a maximalist streak. Rather than aiming to romance with truffle oil and pesto and overtly sweet sauces, more chefs are banking on customers geeking out on the old-school nitty-gritty with them. Chefs Fumio Azumi and Kwan Gong tag-team meals at their Alhambra restaurant Kogane using two styles of shari with different blends of vinegars.

Dancer and chef Yoko Hasebe launched Plant Sushi Yoko, a pickup and delivery service with the best vegan sushi in Los Angeles.

During the pandemic shutdowns, Inoue and Hirano paired on pop-ups, making top-tier versions of chirashi, the boxes of scattered rice jeweled with seafood. When indoor dining resumed, the two chefs wanted to maintain their professional camaraderie. They created a series of Tuesday night collaborations at Kaneyoshi to stay connected and to give L.A.’s most devoted sushi connoisseurs the thrill of a star double-billing.

Two masters forming nigiri shoulder to shoulder is a sight, like watching concert pianists who’ve vanished into a sonata. The rice they serve at their respective restaurants comes from the same century-old shop in Tokyo called Sumidaya. They each make their own shari for their shared evenings; both are potent, but Hirano’s is nearly electric with akazu. They purposefully play with temperatures during the meal, pushing degrees of warmth so the rice, on the taste buds, nearly melts into more assertive seafood.

Their appetizers dazzled, and the dozen-plus nigiri that followed were both main event and finale, a fireworks display slowed to a serene pace. But I was more aware than ever that the shari carried the neta like exceptional crust determines the brilliance of a pizza. Fundamental but not simple.

Maybe rice tastings like Kimura’s should be standard at blowout omakase meals everywhere.

The rice is everything

Sushi Kimura happened to be my first meal on a March trip to Tokyo.

Only air and water may be more vital than rice to life in Japan. It wasn’t so much that Kimura’s shari was the one by which I judged all others, but more that the meal established a frame of mind to which I was extremely attuned for the next seven days.

At omakase dinners, I zeroed in on the minute, satisfying gradations of sour and warmth in the rice. In shari, a bit of sugar can help tease out flavors the way a pinch balances acid in marinara. I found the shari in Tokyo to be broadly saltier than is typical in Los Angeles, pleasantly so. I admired how even nigiri pulled from a refrigerated case in depachika — the wonderful, overwhelming food halls in the basement levels of massive department stores — was made with rice that had been prepared so the grains didn’t have a hint of mushiness and retained a pearly sweetness.

The Sushi Ginza Onodera restaurant group has top-dollar locations around the world, including a 16-seat counter in West Hollywood. Before Tokyo reopened in the fall for tourism, the group opened a more affordable standing sushi bar in upscale Ginza serving some of the same seafood at a third of the price of the omakase restaurants and staffed by skilled chefs working up through the company’s ranks. Surely one of these would fly in Los Angeles.

Ebisu Endo resides on the fourth floor in a building on one of the quieter streets in Shibuya, one of Tokyo’s densest shopping districts. Norihito Endo grew up in the sushi-ya business — his father is also a chef — and he initially left Japan to train as a soccer player in the U.K. before returning to apprentice under Takashi Saito, who is among the world’s most revered. At his own place, Endo blurs tradition and modernism. Before a gorgeous sequence of nigiri, he blanketed soba with deliciously intense bottarga; grilled eel on the spot until its skin crackled; and marinated cucumbers in shio-koji before slicing them into rounds as thin as quarters. Endo’s omakase most reminded me of the L.A. school of sushi-kaiseki.

Was I going to Jiro? That is the question asked by nearly every friend who knew I was headed to Tokyo. No, I did not score one of the hardest reservations on the planet. But through a mutual friend, I met up for lunch with Masuhiro Yamamoto, the food critic in “Jiro Dreams of Sushi” who functioned as the film’s narrator. Yamamoto, who is 75, has eaten thousands of meals at Tokyo sushi-ya; he’s an immovable stickler about Edomae sushi and kodawari, a word used to describe uncompromising craftsmanship.

He didn’t tell me where we were going. We met at a tea shop and then he guided me to the subway. We emerged in Ginza, turned a few corners and stopped in front of the Seiwa Silver Building, a modest skyscraper. On the ground floor, as yet unmarked, was Sushi Kobayashi, a six-seat bar opened in December by Tetsuyasu Kobayashi. We were the only customers.

Yamamoto approvingly pointed out the noren hanging over the counter — square paneled curtains that, in the Edo period, customers used to wipe their hands after finishing their sushi meal. Kobayashi prepared a succinct omakase. All nigiri, no appetizers.

His lineup had akagai (ark shell, or red clam), a seasonal Edomae classic I’d tried elsewhere that week, classically cut in butterflied patterns to yield a texture with both give and crunch. Kobayashi rendered it beautifully. The shari was stained dark as dried blood, the telltale sign of akazu.

We finished with two variations on eel, sweet and savory, and the thinnest, most custardy tamago I’ve had. Yamamoto spoke little but nodded his praise to Kobayashi. We’d had a dozen exactingly prepared nigiri for a lunch that came out to $60 apiece. My dreams of sushi in L.A. momentarily turned to an ode to lineage like this.

My loyalty to Southern California pulled me back from the mists. Of course there is nothing like eating a cuisine at its source: the specificity, the nuances, the details that can never quite be translated. It’s wonderful to visit Tokyo, to be swept away by the culinary heritage and its strictest keepers.

From 20-course omakase tasting menus to snug sushi bars, here’s where to find the best and freshest sushi in Los Angeles.

But Angelenos don’t need to fly across the Pacific for a sushi meal that does justice to the cuisine’s origins — not at this moment in history. Because at the heart of Edomae philosophy is the idea of treating beautiful ingredients with respect. That notion has been alive in California cooking for decades. With sushi, our virtuosos aren’t masking ingredients anymore. They’re flaunting exceptional fish and rice. Nothing more is needed.

Every era of our sushi culture builds on the next. This one has reinforced the bonds with the cuisine’s parentage. Tokyo’s creative omakase practitioners share a form with L.A.’s innovators. Whatever evolutions in sushi follow here, we’ll know the rice stands equal to the seafood. And hopefully the grip on truffle oil has loosened forever.

More to Read

Eat your way across L.A.

Get our weekly Tasting Notes newsletter for reviews, news and more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.